We welcome everyone to Arch Valor’s next series of Tete-a-Tete Talks and we have with us Ar. Yatin Pandya, an architect, author, and activist, with his firm FOOTPRINTS E.A.R.T.H (Environment Architecture Research Technology Housing).

KJ:-Thankyou for having this interview with us. As it is believed that our childhood experiences stick with us for years and continue to influence us, Let’s start by telling us a bit about your background and how has it shaped your philosophy as an architect.

YP:-Life is a series of instances, observations and facts which has a profound impact on the way we think. Growing up in a joint family had led to me to realize the importance of collective consensus where ‘I’ alone don’t matter, these values of sharing and caring prepared me for the future. As a child, it also enabled me to utilize creativity as a tool to address the scarcity of resources which prevailed, I would make toys from waste, so you can say frugality was also one of the virtues embedded early on. One of the instances which would inspire me to be an architect took place when I was just 11 years old. Our house was being built, and the design was created by an engineer, but he practiced as an architect. This entire episode intrigued me and inspired me at the same time.

I began studying architecture as an undergraduate, and then I had the opportunity to further my education abroad. I ended up doing it in Montreal, Canada. During my undergraduate study, a student exchange program led me to the Swiss Institute, it was my first experience traveling outside India and it led me to see and experience life from a different perspective because the way of life in Switzerland as also the culture was unlike what I had experienced back in India. The best part of being overseas was also the fact that it reaffirmed the values I had grown up with. It allowed me to see them in an objective context. When I was able to see the meaning of the values, I inherited from the Indian traditions I was keen to know more about our roots and context.

KJ:-Looking at your each project made me feel like home. Maybe that’s what real sustainability is, feeling comfortable the way you are. What is your interpretation of sustainability and how do you try to bring it into your projects.

YP:-In my view, sustainability starts or is a way of life. So how you conduct your daily routine, what kind of clothes you choose, what kind of food you eat all add up to create a holistic and mutually beneficial package in some ways. For example, in a hot and humid climate, if you dress sparingly, you allow for natural ventilation, and my naive interpretation is that warmer the climate, the spicy the food, so that you have evaporative cooling through perspiration, or you have an accessory, like here in Gujarat, a swing, so that when you swing, what the fan does with the electric power is what you do with the muscle power. This is why, through evaporative cooling, your body perspiration provides you with comfort. So what I’m trying to say is that it’s not a formula. It’s a phenomenon, and a phenomenon for local circumstantial adjustment.

KJ:-Almost every project you undertake has a unique name, rooted in tradition. What drives your choice of projects? Is it because of your love for traditional architecture?

YP:-Each place has its own approach, but all within a broader context of being contextually appropriate, environmentally friendly, and socio culturally driven. While we never turned down a project, our legacy of tradition and sustainability has brought us to where we are now.

What makes it seem to come across is that we have chosen to use some of these lessons and understanding from our traditional wisdom and translate it where and to the extent that its valid and applicable to our project. The Environmental Sanitation Institute, for example, has a very modernistic aesthetic, with exposed brick architecture. It’s a vaulted form, but every decision was based on traditional practices of keeping it resource-efficient. So rather than mourning our losses of or lack of resources, we celebrated it very judiciously, in fact, integrated in our space making.

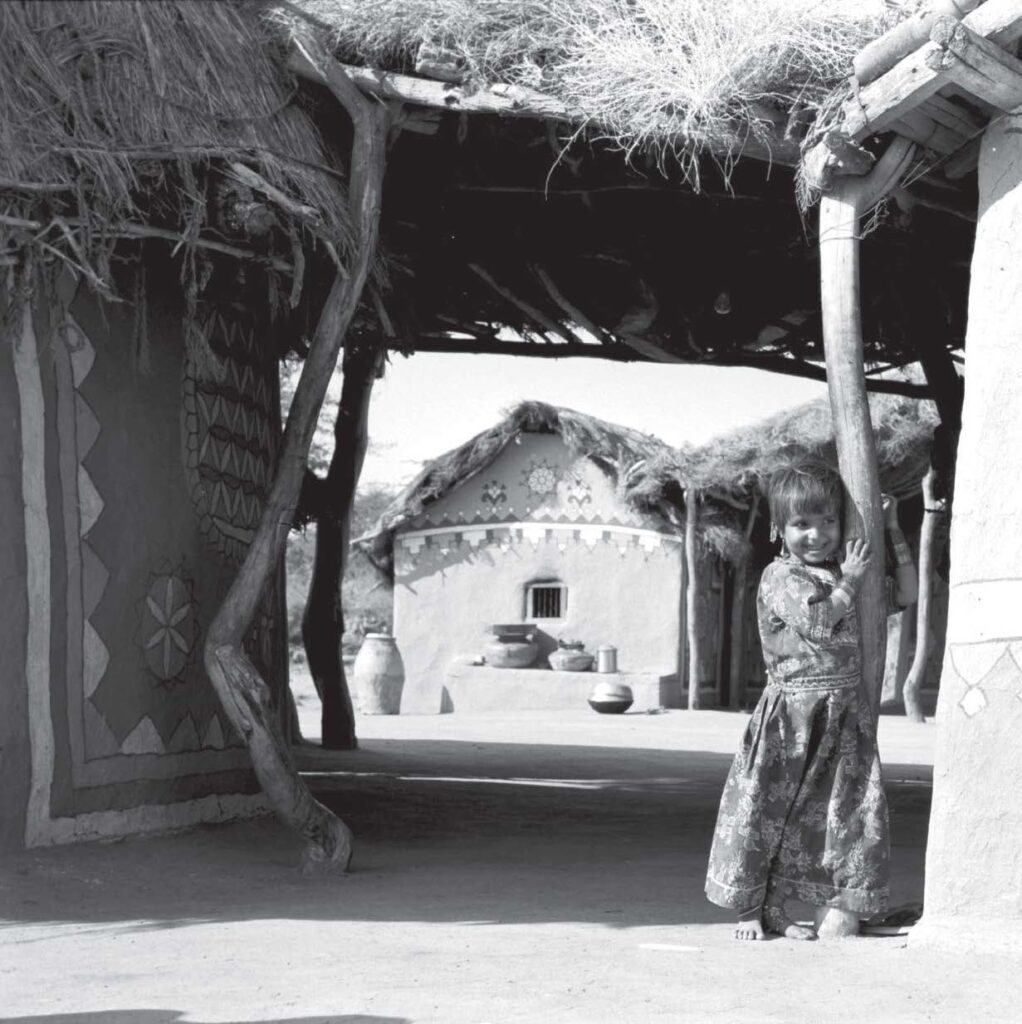

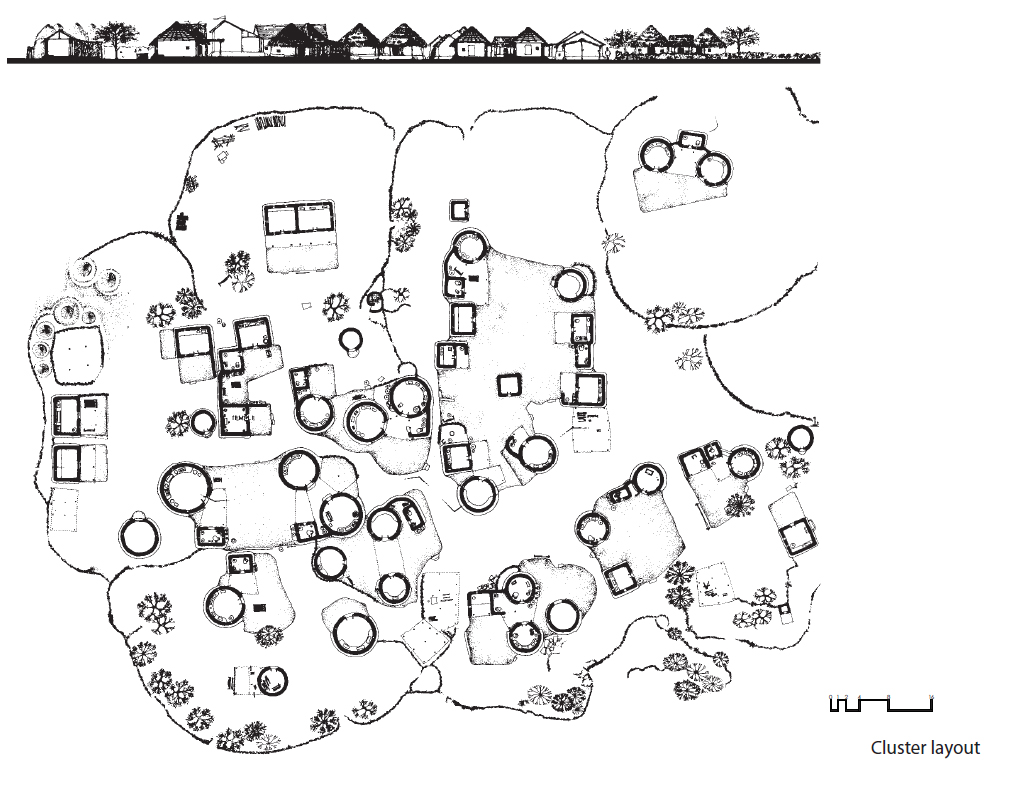

KJ:-Could you walk us through the various stages of your design processes – concept, design, construction and completion of ludiya? What are the most important aspects that you consider while planning, which you feel lacks in modern architecture of today?

YP:-I think design begins with the interpretation of the project, and understanding the context. That way, there are never any preconceived ideas or concerns. Those five filters reflect what we do, so any project or brief that comes our way is run through these lenses, so that we can come up with real approach or direction, more than two words.

What does it mean to kind of society or a context in a broader sense, so in that sense, we interpret that program, then we analyze the site from different perspectives. And then come up with some kind of sequence and story. So that’s where we say that architecture is a narrative. It’s not just coordinating, but attempting to envision a sort of experiential journey.

KJ:-Manavsadna, as its name suggests, is a project reflecting ultimate peace that every human is striving for. Can you shed some light on its design concept?

YP:-As the name tells, Manasadhana is an NGO and the goal is to empower local squatter residents to educate themselves. They wanted to build a Multi Activity Center where in the morning it would be a school, and in the afternoon it was a training center for young ladies to gain employment and empower themselves. Since these were slums or squatter settlements, they had limited resources; they did not have much money, they did not have a lot of resources to build a home. So we used some of the recycled materials, but in a new way.

Having a chance to demonstrate some of our lessons learned over three years of independent research on solid waste management and the dynamics of waste in urban areas was just a coincidence. In Ahmedabad city, for example, we found that in 2005, 2600 tons of waste were produced, and this number has now grown to over 4000 tons daily, but what happens to that waste, hundreds of trucks pick it up from different parts of the city and dump it in a single dump fill site, which has become a seven-story mound of waste. So we studied each of this material, what happens to paper that it is picked up from a house, then it has been sorted and then it goes to each phase, what how much individually, people earn, how many cycles it goes through, for paper, wood, or carton for boxes, metal, glass, or plastic. So we did all these kinds of analysis to understand what really happens to this waste. This is how it was evaluated, through even empirical studies, that we had certification about its structural strength, compression strength, low levels of organic matter, inner material, etc.

KJ:-Being human and innate with emotions, what role does emotions play in your design process?

YP:-This isn’t something you’re acting out, it’s not something you’re trying to do to be a saint or a preacher .It’s ingrained in you, I believe. The kind of upbringing you could not afford to waste, for example, and therefore your value that even if you’re doing things for Ambani, there is no room for waste, is something I bring up again. Ultimately, I think the foundation for any development has to rest on two fundamental tenets or principles: optimal optimization and conservation. One is human to human, that it remains in harmony and the harmonious balance, and other is human to environment. So, when you have these concerns of humanity and environment, I think anything that you create, you filter it through those lenses, and you get an answer, which first satisfies you because those are the concerns which have been true to you not having to adapt, but that’s how you’ve been raised.

KJ:-Can you elucidate your project Ujasiyu. What motivated you to undertake it.

YP:-Ujasiyu in Gujrati means light and ventilation. When you see urban settlements, they’re space constrained, they have resource constrained. So they build their own homes with deep long houses, and three side as a common wall shared with the neighbor. So, there’s only one front side possibility of a window, that also being a narrow house, there is hardly much of a window. As a result, even in May afternoon, they have to run the electric bulb to illuminate the last rooms, because they are always pitched up with corrugated sheets.

Even a fan won’t suffice to relieve the heat, so they used excessive amounts of electric power, and not necessarily even using it, we feel afraid, or it is very gloomy. So we tried address fixing the ventilation through roof because there was no window available.

So we created this dormer kind of a window onto the sloping roof which otherwise they have. So it was on the existing condition simply an in situ adaptation and sort of replacement of that sheet with a dormer sheet which we did with a fiberglass translucent thing which the Mahila Housing Trust from originally save as tree developed as a cottage industry.

With this small design intervention, we were able to influence the lives of people in very different ways, such as the average monthly electricity bill was reduced to 200 Rupees and with less stress on eyes, they were able to work and study for longer hours.

KJ:-Would you like to share the best piece of advice you ever got which also acted as a path breaker for either your career or your life?

YP:-Instead of advice, it came as a bit of learning the hard way. There were several instances in which you were rejected, opposed, or sidelined for wrong reasons. And that gives me a sense of challenge, literally, in fact, not just challenge, but retribution as well. For example, one of my classes, the teachers, I got a very different breed denied expect a lower than what I’d expected, you know, and I went to challenge that, and the professor is just simply to defend itself, he says that it’s a seminar course, and you will not work on. Normally I’m shy in parties, I like to be in the corner. I’m not saying that I didn’t take part in lectures and questions. In fact, I did that the most, but it was a small error which they didn’t want to admit. So I made it a point to be loudest, and that changed me. As you face some of these challenges, do not argue with them, but rather say to yourself, “Yes, I am, so I will analyze it. This is the right way.

The rejections, oppositions, and sidelines I encountered gave me a sense of challenge.

-Ar.Yatin Pandya

KJ:-Your two most famous books “Concepts of Space in Traditional Indian Architecture” and ‘Elements Of Space Making” examine the diversity of spaces in India. Can you give us a brief overview of the books and what challenges you faced while writing them.

YP:-When we began our research, we did not have any support. So we continued to do it on the back burner. So it was more of a personal quest to try and understand the non-standards that are relevant to India. The buildings of yesterday continue to inspire people, and most of the tourism in India is to look at the ruins, which are not even available to visit. Yet we get excited about it. It’s obsolete, yet we feel passionate about it. Even by virtue of being functionally obsolete, even by virtue of transcending that time and kind of context, they still become places of interest. You can even today, experientially engage with them, even without historic background and without guided stories, purely as a space in which you can enjoy yourself and feel its impact. There was more of a search on those kinds, that what are those principles that we can imbibe today, that we do not have to emulate the elements, the materials, or the technique, but on the experiential level, how do we create these spaces.

I came up with a few of these approaches to design, and one of them was the theme of sequential unfolding, where it engages you like a treasure hunt, and you go, and then once you reach the destination, the next clue, Indian architecture has been that whole layering of spaces, having a number of thresholds, and you have to experience it.

The concept of space was a search for a kind of aesthetic perception about the ageless architecture you find in yester years. The elements of space making were, again, an investigation that all these are basically, if you examine the postmortem and assembly of the components, and each element has a specific task. I thought it’s a good idea to understand the primary role these elements play, like windows have been the eye of the wind, same way sunscreen, what iron is, air passage.

KJ:-Being an author of many books and research papers, I would like to know your thoughts on documenting and writing architecture. Why do you feel communicating about architecture is so important and where do you feel we are lacking as a nation.

YP:-This kind of training or mentality can be hard to cultivate. Firstly, as I mentioned, the architecture of yester year or the architecture of different regions outside the vernacular has been so diverse. Secondly, the architecture of those times had those three performance parameters of timeless aesthetics, social relevance, and environmental sustainability. To understand them, we must acknowledge that they exist, provide us with some kind of document, and then we must analyze and interpret.